Death on the Nile

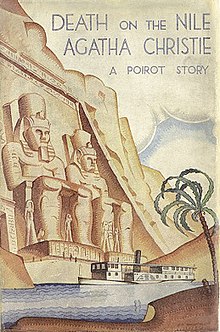

Dust-jacket illustration of the first UK edition | |

| Author | Agatha Christie |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | Robin Macartney |

| Language | English |

| Series | Hercule Poirot |

| Genre | Crime novel |

| Publisher | Collins Crime Club |

Publication date | 1 November 1937 |

| Publication place | United Kingdom |

| Media type | Print (hardback & paperback) |

| Pages | 288 (first edition, hardback) |

| Preceded by | Dumb Witness |

| Followed by | Appointment with Death |

Death on the Nile is a work of detective fiction by British writer Agatha Christie, published in the UK by the Collins Crime Club on 1 November 1937[1] and in the US by Dodd, Mead and Company the following year.[2][3] The UK edition retailed at seven shillings and sixpence (7/6)[4](equivalent to £31 in 2023) and the US edition at $2.00 (equivalent to $42 in 2023).[3] The book features the Belgian detective Hercule Poirot. The action takes place in Egypt, mostly on the River Nile. The novel is unrelated to Christie's earlier (1933) short story of the same name, which featured Parker Pyne as the detective.

Plot

[edit]Successful socialite Linnet Doyle née Ridgeway approaches Hercule Poirot while he is vacationing in Aswan to board the steamer "Karnak," which will tour along the Nile River from Shellal to Wadi Halfa. She wants to commission him to deter her former friend Jacqueline de Bellefort from hounding and stalking her. Linnet had recently married Jacqueline's ex-fiancé, Simon Doyle, which has made Jacqueline bitterly resentful. Poirot refuses the commission and unsuccessfully attempts to dissuade Jacqueline from pursuing her plans. Simon and Linnet secretly follow Poirot to escape Jacqueline but find she has learned of their plans and boarded ahead of them. The other Karnak passengers include Linnet's maid Louise Bourget; her trustee Andrew Pennington; romance novelist Salome Otterbourne and her daughter Rosalie; Tim Allerton and his mother; elderly American socialite Marie Van Schuyler, her cousin Cornelia Robson and her nurse Miss Bowers; outspoken communist Mr Ferguson; Italian archaeologist Guido Richetti; solicitor Jim Fanthorp; and Austrian physician Dr Bessner.

While visiting Abu Simbel when Karnak stops there, Linnet narrowly avoids being crushed to death by a large boulder that falls from a cliff. Jacqueline is suspected of pushing the boulder off the cliff, but she was aboard the steamer at the time of the incident. At Wadi Halfa, Poirot's friend Colonel Race boards the steamer for the return trip. Race tells Poirot that he seeks a murderer among the passengers.

Jacqueline expresses her bitterness toward Simon the next night in the steamer's lounge. She shoots him in the leg with a pistol while furious, but she immediately feels regret and kicks the gun away. The two other people present, Fanthorp and Cornelia, take her to her cabin. Simon is shortly brought to Dr Bessner's cabin for treatment for his injury. Fanthorp looks for Jacqueline's pistol but reports that it has disappeared. The following morning, Linnet is found dead, shot in the head, while her valuable string of pearls has disappeared. Jacqueline's pistol is recovered from the Nile; it was wrapped in a velvet stole that Miss van Schuyler had reported missing the day before. Two shots have been fired from the pistol.

While interviewing Louise in the cabin where Simon is resting, Poirot notes the oddness in the words she uses. Miss Bowers returns Linnet's pearl necklace, which Miss Van Schuyler, a kleptomaniac, stole. However, Poirot realises it merely imitates Linnet's genuine necklace. He notes two nail polish bottles in the victim's room, one of which intrigues him. Louise is then found stabbed to death in her cabin. Mrs Otterbourne later meets with Poirot and Race in Simon's cabin, claiming she saw who killed the maid, to which Simon declares his surprise. Before revealing who it is, she is shot dead from outside the cabin.

Poirot soon confronts Pennington over his attempted murder of Linnet by pushing the boulder off the cliff; Pennington had speculated unsuccessfully with her inheritance and came to Egypt upon learning of her marriage to trick her into signing documents that would exonerate him. However, he claims he did not murder anyone despite his revolver being used in Mrs Otterbourne's murder. Poirot recovers Linnet's genuine pearls from Tim, who he exposes as a professional thief. Tim had substituted an imitation string of pearls for the genuine necklace. Race realizes Richetti is the man he is looking for.

Poirot tells Race, Bessner, and Cornelia that Simon killed Linnet. Jacqueline planned the murder; the pair are still lovers. Linnet had deliberately and unashamedly tried to take Simon away from Jacqueline, and Simon decided to go along with it so he could murder her for her money later. Afraid of the none-too-bright Simon being caught and executed, Jacqueline concocted what she thought was a foolproof plan. On the night of the murder, Jacqueline deliberately missed Simon, who faked his leg injury with red ink. Jacqueline diverted Fanthorp and Cornelia, so Simon took the pistol, went to Linnet's cabin, and shot her. He placed the nail polish bottle that had contained the red ink on Linnet's washstand, then returned to the lounge and shot himself in the leg. Simon used the stole to silence the pistol, loaded a spare cartridge to make it seem that only two shots were fired, and threw the gun overboard.

Louise had witnessed Simon entering Linnet's cabin that night and hinted at this to Simon when Poirot was interviewing her, planning to blackmail him. Jacqueline, again in an attempt to protect her lover, stabbed Louise to death. Mrs Otterbourne saw Jacqueline entering Louise's cabin; when she went to tell Poirot, Simon had raised his voice to alert Jacqueline in the next room. She immediately shot and killed Otterbourne before the truth could be revealed. Poirot confronts Simon, who confesses. He is arrested, as are Jacqueline and Richetti. As the steamer arrives back in Shellal and the passengers disembark, Jacqueline shoots Simon and herself with another pistol so they may escape the gallows. When pressed, Poirot reveals he had always known she had a second pistol but had chosen to allow her to take her own life.

Reception

[edit]Contemporary reviews of the book were primarily positive. The short review in the Times Literary Supplement concluded by saying, "Hercule Poirot, as usual, digs out a truth so unforeseen that it would be unfair for a reviewer to hint at it."[5]

The Scotsman review of 11 November 1937 finished by saying that "the author has again constructed the neatest of plots, wrapped it round with distracting circumstances, and presented it to what should be an appreciative public."[6]

E. R. Punshon of The Guardian in his review of 10 December 1937 began by saying, "To decide whether a writer of fiction possesses the true novelist's gift it is often a good plan to consider whether the minor characters in his or her book, those to whose creation the author has probably given little thought, stand out in the narrative in their own right as living personalities. This test is one Mrs Christie always passes successfully, and never more so than in her new book."[7]

In a later review, Robert Barnard wrote that this novel is "One of the top ten, in spite of an overcomplex solution. The familiar marital triangle, set on a Nile steamer." The weakness is that there is "Comparatively little local colour, but some good grotesques among the passengers – of which the film took advantage." He notes a change in Christie's novels with this plot published in 1937, as "Spies and agitators are beginning to invade the pure Christie detective story at this period, as the slide towards war begins."[8]

References to other works

[edit]- In Chapter 12, Miss Van Schuyler mentions to Poirot a common acquaintance, Mr. Rufus Van Aldin, known from The Mystery of the Blue Train.

- In Part II, Chapter 21 of the novel, Poirot mentions having found a scarlet kimono in his luggage. This refers to the plot in Murder on the Orient Express.

- When Poirot meets Race, Christie writes: "Hercule Poirot had come across Colonel Race a year previously in London. They had been fellow-guests at a very strange dinner party—a dinner party that had ended in death for that strange man, their host." It refers to the novel Cards on the Table.

- About to reveal the identity of the murderer, Poirot credits the experience recounted in Murder in Mesopotamia with developing his methods in detection. He muses: "Once I went professionally to an archaeological expedition—and I learnt something there. In the course of an excavation, when something comes up out of the ground, everything is cleared away very carefully all around it. You take away the loose earth, and you scrape here and there with a knife until finally your object is there, all alone, ready to be drawn and photographed with no extraneous matter confusing it. This is what I have been seeking to do—clear away the extraneous matter so that we can see the truth..."

Adaptations

[edit]Theatre

[edit]Agatha Christie adapted the novel into a stage play which opened at the Dundee Repertory Theatre on 17 January 1944[9] under the title of Hidden Horizon. It opened in the West End on 19 March 1946 under the title Murder on the Nile and on Broadway on 19 September 1946 under the same title.

Television

[edit]A live television version of the novel under Murder on the Nile was presented on 12 July 1950 in the US in a one-hour play as part of the series Kraft Television Theatre. The stars were Guy Spaull and Patricia Wheel.

An adaptation for the television series Agatha Christie's Poirot was made for the show's ninth series in 2004. It starred David Suchet as Poirot. Guest stars included Emily Blunt as Linnet, JJ Feild as Simon Doyle, Emma Griffiths Malin as Jacqueline, James Fox as Colonel Race, Frances de la Tour as Salome Otterbourne, Zoe Telford as Rosalie Otterbourne and David Soul as Andrew Pennington. The episode was filmed in Egypt, with many of the scenes filmed on the steamer PS Sudan.

Film

[edit]The novel was adapted into a 1978 feature film, Death on the Nile, starring Peter Ustinov for the first of his six appearances as Poirot. Others in the all-star cast included Bette Davis (Miss Van Schuyler), Mia Farrow (Jacqueline de Bellefort), Maggie Smith (Miss Bowers), Lois Chiles (Linnet Doyle), Simon MacCorkindale (Simon Doyle), Jon Finch (Mr Ferguson), Olivia Hussey (Rosalie Otterbourne), Angela Lansbury (Mrs Otterbourne), Jane Birkin (Louise), George Kennedy (Mr Pennington), Jack Warden (Dr Bessner), I. S. Johar (Mr Choudhury) and David Niven (Colonel Race). The screenplay differs slightly from the book, deleting several characters, including Cornelia Robson, Signor Richetti, Joanna Southwood, the Allertons, and Mr. Fanthorp. Tim Allerton is replaced as Rosalie's love interest by Ferguson.

Another film adaptation, also called Death on the Nile, directed by and starring Kenneth Branagh, was released on February 11, 2022. It is the follow-up to the 2017 film Murder on the Orient Express. Some characters and details are either omitted or differ from the novel, while the elements of the central murder remain unchanged. Tim Allerton's replacement is Bouc, who also has his mother Euphemia with him. Salome Otterbourne is now a jazz singer and no longer a drunk, while Rosalie is her niece whom she adopted. Bouc is the third person killed instead of Salome Otterbourne. Linnet's lawyer Andrew is now also her cousin, and Mrs. Van Schuyler and Miss Bowers are a lesbian couple. Mrs. Van Schuyler is also the godmother of Linnet. All the suspects are friends of the married couple who have invited them to their honeymoon celebration. A World War I romance is invented for Poirot, and it is hinted that Poirot and Otterbourne have romantic feelings for each other. It also stars Gal Gadot, Emma Mackey, Armie Hammer, Annette Bening, among other stars.

Radio

[edit]The novel was adapted as a five-part serial for BBC Radio 4 in 1997. John Moffatt reprised his role of Poirot. The serial was broadcast weekly from Thursday, 2 January to Thursday, 30 January from 10.00 am to 10.30 pm. All five episodes were recorded on Friday, 12 July 1996, at Broadcasting House. Enyd Williams was the director and Michael Bakewell was in charge of adapting it.

Video game

[edit]Death on the Nile was turned into a hidden object PC game, Agatha Christie: Death on the Nile, in 2007 by Flood Light Games, and published as a joint venture between Oberon Games and Big Fish Games.[10] The player takes the role of Hercule Poirot as he searches various cabins of the Karnak for clues, and questions suspects based on information he finds.

Graphic novel

[edit]Death on the Nile was released by HarperCollins as a graphic novel adaptation on 16 July 2007, adapted by François Rivière and Solidor (Jean-François Miniac) (ISBN 0-00-725058-4). This is a translation of the edition that Emmanuel Proust éditions first published in France in 2003 under the title "Mort sur le Nil."

Partial publication history

[edit]The book was first serialized in the US in The Saturday Evening Post in eight installments from 15 May (Volume 209, Number 46) to 3 July 1937 (Volume 210, Number 1) with illustrations by Henry Raleigh.

- 1937, Collins Crime Club (London), 1 November 1937, Hardback, 288 pp

- 1938, Dodd Mead and Company (New York), 1938, Hardback, 326 pp

- 1944, Avon Books, Paperback, 262 pp (Avon number 46)

- 1949, Pan Books, Paperback, 255 pp (Pan number 87)

- 1953, Penguin Books, Paperback, (Penguin number 927), 249 pp

- 1960, Fontana Books (Imprint of HarperCollins), Paperback, 253 pp

- 1963, Bantam Books, Paperback, 214 pp

- 1969, Greenway edition of collected works (William Collins), Hardcover, 318 pp

- 1970, Greenway edition of collected works (Dodd Mead), Hardcover, 318 pp

- 1971, Ulverscroft Large-print Edition, Hardcover, 466 pp ISBN 0-85456-671-6

- 1978, William Collins (Film tie-in), Hardback, 320 pp

- 2006, Poirot Facsimile Edition (Facsimile of 1937 UK First Edition), HarperCollins, 4 September 2006, Hardback, ISBN 0-00-723447-3

- 2007, Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers, e-book ISBN 978-1-57-912689-6

- 2011, HarperCollins, e-book ISBN 978-0-06-176017-4

- 2011, William Morrow, Paperback, 352 pp ISBN 0-06207-355-9

- 2020, HarperCollins, Hardback, ISBN 0-00838-682-X

References

[edit]- ^ The Observer 31 October 1937 (Page 6)

- ^ John Cooper and B.A. Pyke. Detective Fiction – the collector's guide: Second Edition (Pages 82 and 86) Scholar Press. 1994. ISBN 0-85967-991-8

- ^ a b American Tribute to Agatha Christie

- ^ Chris Peers, Ralph Spurrier and Jamie Sturgeon. Collins Crime Club – A checklist of First Editions. Dragonby Press (Second Edition) March 1999 (Page 15)

- ^ "Review". The Times Literary Supplement. 20 November 1937. p. 890.

- ^ "Review". The Scotsman. 11 November 1937. p. 15.

- ^ Punshon, E R (10 December 1937). "Review". The Guardian. p. 6.

- ^ Barnard, Robert (1990). A Talent to Deceive – an appreciation of Agatha Christie (Revised ed.). Fontana Books. p. 192. ISBN 0-00-637474-3.

- ^ University of Glasgow page on play

- ^ Bigfishgames.com Archived 5 July 2007 at the Wayback Machine

External links

[edit]- Death on the Nile at the official Agatha Christie website

- Murder on the Nile (1946 production) at the Internet Broadway Database

- Murder on the Nile (1950 television play) at IMDb

- Death on the Nile (1978 film) at IMDb

- Death on the Nile (2004 episode of Poirot) at IMDb

- 1937 British novels

- Hercule Poirot novels

- Novels set in Egypt

- Novels set in London

- Novels set on ships

- Novels set on rivers

- Fiction about uxoricide

- Works originally published in The Saturday Evening Post

- Novels first published in serial form

- Collins Crime Club books

- British novels adapted into plays

- British novels adapted into films

- British novels adapted into television shows

- Nile in fiction

- Abu Simbel